Steven Pinker and the Four-Letter Word

I was completely unprepared for what happened last Thursday night.

Steven Pinker came to town to present his latest book, and I thought this column would be about our different theories. Or about how he’s hyper-rational and that hyper-rationality doesn’t work in the real world. His theory almost exists above humanity in a mathematical perfection that rarely matches what happens on planet Earth. It’s not that it’s not true. Of course, there’s truth to everything he says. The incidence of violence has gone down dramatically. Humans are wired to learn language in some way—if it were not true, we would not call it human language.

But as an emergentist, I think the world is more complicated than the mathematical simplicity with which he describes how things happen. It might be true that physical violence is lower than it was before, but humans suffer anyway. There’s relational aggression, the cortisol released when a car cuts in front of you on the freeway, the fear of an imperceptible virus spreading like an eight-foot wave about to swallow you up on the beach. Yes, things change, but we change too. Our brains adapt in multiple ways. Every time Steven Pinker makes what appears to me to be a single-minded assertion, I always hear a but in my head, a skepticism that it sounds too good to be true.

I thought this post was going to be about that. It almost was. And then I felt something completely different.

I was thrown off by his unbridled optimism.

It’s not an optimism I would ever have gleaned from the pages of his books or from his more academic work. Even though Steven Pinker and I may not see eye to eye on how language works or how rational we are as humans, he truly believes the world is a good place. He hopes it will become a better place. And his books, to me, had always seemed overly cerebral, however elegantly written. None of that ever approximated the hopefulness I saw that evening.

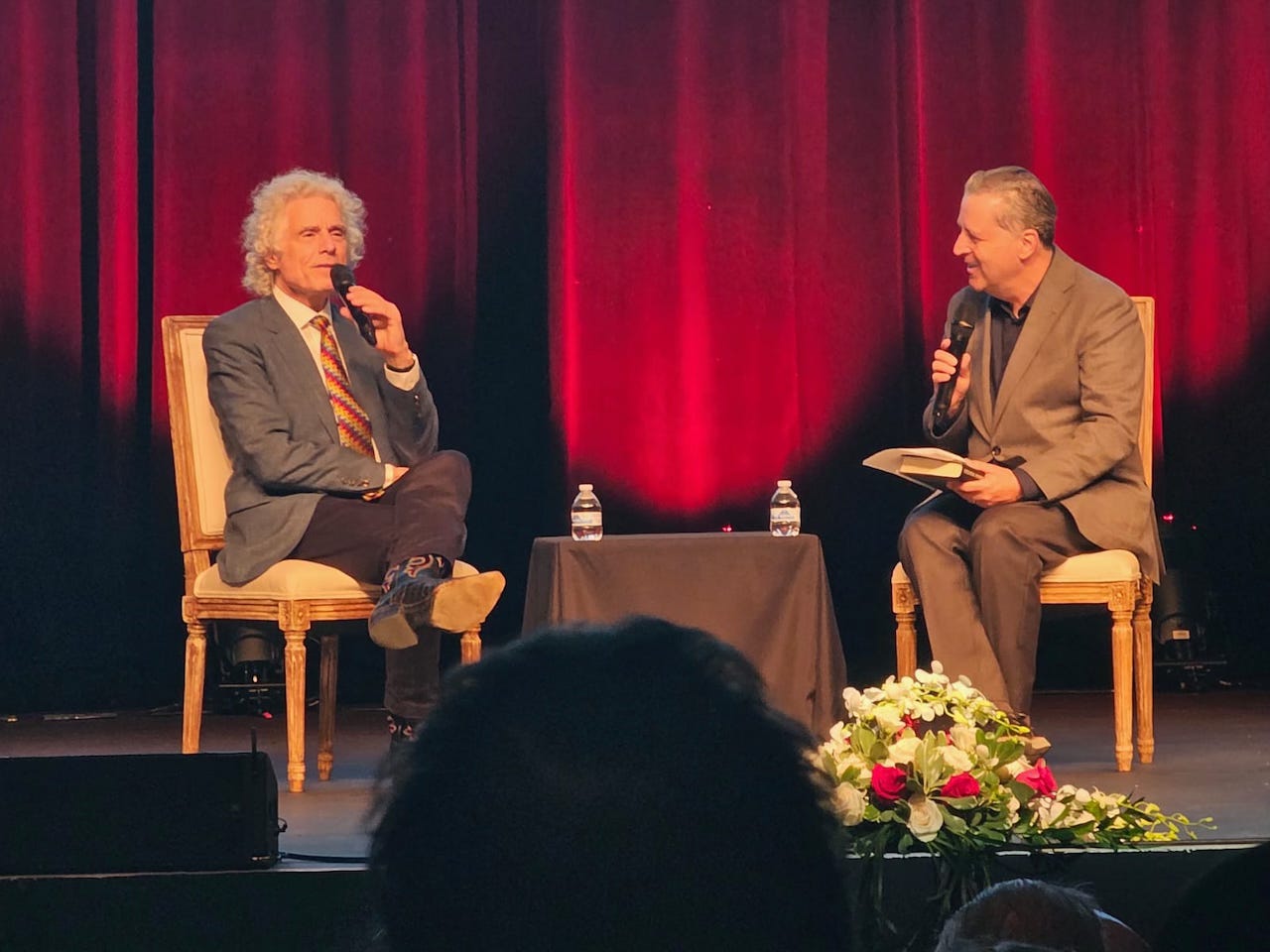

His presentation was a mix of ideas, anecdotes and several well-timed jokes. It ended surprisingly fast and it was time for me to lead the Q&A.

I went up to the stage. I took the chair on his left while he took the chair on my right. We hadn’t rehearsed this at all. We just knew, proof that his concept of common knowledge exists in real time between two strangers who had just met a few minutes earlier.

We touched on a lot of topics—social media, the fractionation of media versus government control, cancel culture. His answers were quite clear: the government shouldn’t tell people what to think. The government doesn’t always get it right, and that’s a problem. From his perspective, cancel culture hurts people by telling them they can’t state certain opinions on both sides of the political spectrum.

As the evening drew to a close, I realized that asking him about common knowledge over and over again wasn’t going to take us much further. So I asked him a different question:

How is a book born?

The ways that books were born varied. Sometimes one book grew from another. A very short section on language in one book led to Rationality. Another time he wondered if violence was actually diminishing. He posted his idea on social media and began to get feedback from people in very different fields showing him that the incidence of violence, in fact, was diminishing. Some books contained the seeds of the next. Others were ideas that he vetted with those around him.

The highlight of the evening popped out of nowhere. As he talked about all his books, it occurred to me that he might feel differently about them. Maybe some were natural births and others perhaps much more effortful, a literary cesarean.

So I asked him:

What was your favorite book?

In that moment, he let down his guard. A huge smile came across his face. For a moment, he was no longer Steven Pinker, Professor, National Academy of Science Member, Author. The knowledgeable discussion of all these complicated topics melted away in joy. He was like a parent talking about his favorite child, the one who was just like him and who understood him and he them.

“Enlightenment Now,” he said. “It was my favorite book. It was the one where I really talked about what I felt. That was me.”

In that moment, what I—and what the audience—felt was his love. Love for writing, for expressing ideas, for moving beyond the jokes and interesting examples to something deeper.

Years ago, I was visiting Viorica Marian, a professor at Northwestern and expert on cognition and bilingualism. She invited a group of graduate students from her lab to lunch. They were curious and asked me: How do you make it so long in a career? What’s the secret of your success? I was flattered by the question because, of course, there’s always the idea that more could have been done, that there are still things we want to achieve. But I told the students it’s a four-letter word:

LOVE.

It’s the only way we can truly persist for so long at something.

In Pinker’s discussion of Enlightenment Now, in the way his face lit up and the way he looked at the audience, I could see that he had that too.

Perhaps the greatest lesson of this evening was not about rationality or intellectual discourse. It was about the love that makes all thinking worth doing.

So I imagined. Sometimes the unexpected props up in unexpected ways and oops what a surprise. Maybe but just maybe, those that asked you to mediante had an inkling that somewhere at some point the unspoken energy of connection plays its tune.

Wow.... Nice to hear. I had not understood that aspect about Pinker - his optimism, although, yes, certainly, that is a theme of Englightenment Now. Also, great to hear that Pinker was calm and even-handed about cancel culture. Because people have tried to cancel Pinker because he sometimes comes across as not being sufficiently woke. https://www.spiked-online.com/2020/07/09/steven-pinker-wont-be-cancelled-but-you-could-be/